|

Columns |

![]()

Columns: May

"I asked him [Noel Cassidy, former IRA blanketman] what it was like, and how it could be so bad that 420 men could allow Sands, the best and brightest of their young lot, the Hon. Member of Parliament for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, to shrivel up like a turnip.

He told me. There was the sun of the Easter Rising in his eyes. There was also a feeling of grief and horror and a sense of sorrow agreed upon...

He told a tale of duplicity and Indian-giving that led to the current

gruesome crisis. In the Maze, rapists who have been described by representatives

of the Crown as Ordinary Decent Criminals are allowed to play sports while

Irish Republican prisoners lie naked in cells with walls smeared with

excrement. The British say this is the stubborn rebels' punishment for

not admitting they are your regular crooks, as in the Mafia."

Interview with

former IRA prisoner Noel Cassidy

"The Day They Voted on Death by Starvation"

by Warren Hinckle

San Francisco Chronicle, 1

May 1981, 4

"Bobby Sands had a right to do what he wanted with

whatever life was left in him. But…you had to wonder if the 27-year-old

IRA man has done the right thing…If they've got too much of anything in

this tiny green-hill country, they've got too many dead heroes. What they

lack is enough live politicians with the gumption to reach out beyond

their own narrow religious or political constituencies to fold in some

support from the other side."

"The land of too many

sad songs" by David Nyhan

Boston Globe, 5 May 1981,

15

"It is often said there is too much history in Ireland. But there is no history now, just lies, distortion, and sham. And it is to this that the sad and awful death of Bobby Sands will add. He is myth now, part of an elaborately cultivated contrivance to conceal an ugliness about ourselves we dare not face: It is the Irish who are doing the damage to the Irish. We are our own oppressors.

We have, of course, constructed ingenious strategems to evade the truth, even to the point of denying who we are, of denying the past. We have, instead, a set of myths, an idea about Ireland that satisfies our need to sublimate the past, that compensates for the harsh, uncomforting reality of what we have done to each other in the name of God, and in the name of country.

AIA Dig. ID 0017PL02 |

All of history is viewed through the prism of the Easter Uprising of

1916. It is refracted. What does not fit the myth of enduring struggle

against the British oppressor is discarded. What is left are only fragments

of truth."

"Too Irish to admit

it, we are our own enemies"

by Padraig O'Malley

Chicago Tribune, 8 May

1981, 1-22-5

"It is odd, regrettably so, that so many Americans

have bought the British line that Sands and the other dissidents aren't

worth talking to. We have been forgetful. It was only a little more than

two centuries ago that dissidents in the American colonies joined as a

revolutionary force to overthrow the British presence."

"The third combatant"

by Colman McCarthy

Boston Globe, 9 May 1981,

11

"What is proved by the death of Bobby Sands?

That there are men in Ireland willing to die in the cause of national

unity. But we knew this already. Hundreds, on both sides, have been killed,

and have killed, to further their political objectives. To offer to die

for one's cause, however, is not the equivalent of a) ennobling that cause;

or b) furthering it."

"The Lesson of

Bobby Sands" by William Buckley

San Francisco Chronicle, 10

May, 1981, B-8

"Since Sands' death, the world has been turning

its attention elsewhere. The Pope got shot, war may break out any day

in the Mideast, and Belfast has not blown up in the kind of civil strife

some had predicted. If Thatcher's gamble was to ride out the first couple

of hunger-strike deaths and respond with massive security patrols, then

she has won her gamble."

"Ulster: A call unanswered"

by David Nyhan

Boston Globe, 10 May 1981,

19

"Throughout the fast of Bobby Sands, the member of Parliament-elect now dead of terminal patriotism and mourned by his people as a hero, British leaders never failed to define him as a convicted terrorist. We were asked to believe that he was a low-life Paddy, destructive to the peace that the brave British Army was valiantly trying to keep.

But what if the definition of Sands is enlarged, as it should be, and

we include not only the offenses he is alleged to have committed but also

the government-sanctioned violence against Northern Ireland's Catholic

minority from which Sands and so many other young men like him emerged?

The picture then, as would be expected, is much different."

"Misplaced Energies"

by Colman McCarthy

Washington Post, 10 May

1981, F-4

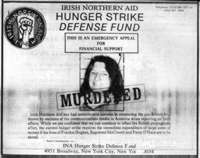

AIA Dig. ID 0024PL03 |

"The death of Bobby Sands will change little

in Northern Ireland. It may seem so at first, upon the evidence of headlines

and television images. There may be death, brutal senseless deaths, and

violent demonstrations, more violent and more widespread perhaps than

any in recent years, but after a while, after a few weeks, the province

will sink back into its apparent hopelessness."

"In troubled Ireland,

the enemy is history" by

Thomas Flanagan

Boston Globe, 11 May 1981,

15

"Above all else, to be Irish is to be Catholic: genuflecting, chest-pounding, church-going Catholic. The devout Catholicism of the Irish people is a phenomenon to move the stoutest skeptic, even when he is full of Guinness and song in the Dublin night. Under cruel English occupation the Irish fought for their religion. They suffered grim privation because of it. And today, they observe it fervently in their polity and in their churches.

Life in Ireland is Catholic. When the pope's emissary, Msgr. John Magee,

visited Bobby Sands and his fellow IRA terrorists, he reiterated the obvious

- the church disapproves of suicide. Had Bobby Sands been an Irish patriot

rather than a terrorist and friend of the PLO, he would have followed

the moral strictures of his church."

"Of Patriots and Terrorists"

by R. Emmett Tyrrell, Jr.

Washington Post, 11 May

1981, A-13

"Some day soon, the gable-ends on the Falls [Road in Belfast] will read 'Remember Bobby Sands.' Sands will in that way enter history, his anguish translated into a slogan on those walls which are the textbooks of Northern Ireland. But in a sense - in [James] Joyce's sense - he was in history from the moment he began his fast. His supporters have been reminding us of the Irish tradition of such martyrdom, evoking history as a context for his deed…

Perhaps, being Irish, such things are central to their sense of identity.

Britain has served them ill, and perhaps herself as well, by conspiring

with the IRA to bestow upon them so ambiguous an icon as the body of Bobby

Sands."

"Irish are living historical

fiction" by Thomas Flanagan

Chicago Tribune, 11 May

1981, 1-22

"The deaths of Bobby Sands and Francis Hughes demonstrated once again the curious romantic mist that obscures some people's vision when they consider the Irish Republican Army. The Massachusetts House passed a resolution honoring Sands. Others treated his self-imposed death as a tragedy akin, say, to the untimely loss of a war poet.

Both were about as poetic as the characters in the old gangster movies.

They had long records of criminal violence. Ah but the glorious cause,

the sympathizer will say. Some glory. Some cause."

"A Tragic Irish Mist"

by Anthony Lewis

San Francisco Chronicle, 15

May 1981, 64

"Sands' election to the House of Commons on April 10 opened up certain possibilities for the British Government had they wanted to take advantage of them. After he became Robert Sands MP, the British no longer need have considered him as an isolated "extremist"-one with whom it would have been embarrassing to have to deal; no-he was a man with a constituency, and that constituency should have been recognized by the authorities.

In a way, it would have let Thatcher off the hook. Often the government has said to the paramilitaries "use the ballot box, then we can consider your views." This is precisely what Sands did. He gave the government the opportunity it had frequently claimed it wanted. And what was the result? The government ignored the result of the very process it for so long had been extolling.

By so doing it has probably only succeeded in confirming the Provisional IRA's commitment to violence.

As the other hunger strikers continue to deteriorate, Thatcher continues

to parrot the extraordinarily hypocritical line: 'A crime is a crime is

a crime.' This is not so, and the government knows it. Apart from the

notorious failure of the authorities to apply that doctrine to their won

security forces, as well as to a certain member of Thatcher's cabinet

responsible for sanctioning illegal acts in 1971 it does not take into

account the precedents which exist in English prison rules and practices."

"After Sands-the Death

of Compromise?" by Jack Holland, Analysis

Irish Echo, 16 May 1981, 2

"I was on a bus with people from the Lower Falls ghetto of Belfast who were going to the burial of hunger striker Francis Hughes last Friday as other Catholics go to London. The English called him a terrorist and a suicide artist, but to these people he was a war hero and a saint…

From every direction rivers of people poured down the roads toward the

Hughes family home where the open casket of the shrunken-faced hunger

striker had been waked…A confused French journalist asked how big he should

say the crowd was; I told him to write that it looked like an IRA Woodstock."

"Under Attack with

IRA Mourners" by Warren Hinckle

San Francisco Chronicle, 20

May 1981, 6

"'Perfidy' is the only word to describe the attitude of all British parties towards the H-Block hunger strikers...

The propaganda war will rage as well. 'A crime is a crime' Margaret Thatcher will say as the MPs drone, 'hear, hear.' The hunger strikers will be described as 'murderers,' 'terrorists,' 'criminals!'

I did not know Frank Hughes. I may not agree with the violence he practiced.

But I understand it. The British, and indeed many southerners do not.

They have little experience of the gruesome statelet called "Northern

Ireland," the political slum of Europe. They cannot possibly understand

how one can endure so much."

"Mrs. Thatcher has

earned her bad press," Dublin Report by John A. Kelly

Irish Echo, 23 May 1981, 2

"The funeral of Patsy O'Hara, a 23-year-old weaver and the latest of the hunger strikers to die, took place while a theological dispute was raging over whether he and his three comrades had committed suicide.

During the funeral, the orations the brother of the deceased gave a talk that was the moral equivalent of Paisley's diatribe.

John O'Hara, anxious to make the event a political occasion and an IRA

recruiting rally, was enjoying the celebrity of the moment. He read from

a single-spaced, three-page screed a harrowing account of O'Hara's final

hours."

"Ulster: Trapped in

the Past" by Mary McGrory

Boston Globe, 28 May 1981,

13